When Clara and I first came to this part of the country in 1969, land was cheap. We had spent a week driving around up North, and on our way back to Iowa we came through and decided to retire here: Flathead Lake, Montana, the east side. It was the end of summer and the cherry crop had already been picked, but we fell in love with the orchards, the way they go right down to the shore, and the way that the mountains look, so close. "Sam," Clara said to me, "wouldn't it be a fine thing to live here, like a vacation all year long?"

We stayed at the state campground for five days, and that was Clara's base of operations. From there she planned, made notes and used the pay phone to call real estate agents, landowners and, finally, the Jerognsons, who sold us this place -- a ramshackle dock, an old wooden house and four acres of cherry trees. It took all our savings, and, of course, we had to sell our house in Des Moines.

The kids didn't mind. Why should they have? Sue was living in New York then and John in Houston. "It will be a great place for us all to get together in the summer," Clara said on the phone when we broke the news to them. "You can help your father with the cherry harvest," she told John. "Sue," she said when she called New York, "you'll love the lake. It's beautifully clear."

We both knew about winters, but our first one was rough. The cold didn't bother us -- we were prepared for it -- but the isolation did. The road was snowed in much of the time, and most of the people we had met in the summer moved away for the winter. Clara and I made big fires in the stove, played a lot of cards and planned what we would do with our four acres of cherries.

That spring, when the blossoms came out and the breezes off of the lake were fresh and warm, I felt like a kid again. Clara and I were only fifty, but we had both worked many hard years; we were happy that spring. I read books on orchard management, built a tool shed, pruned the trees, repaired the dock. Clara made friends with all the neighbors up and down the lake for miles -- she wasn't going to spend another winter alone with me as her only card partner -- and she fixed up the house, put in a garden, made herself a home. When the weather started to get hot, we spent the afternoons on the dock sipping lemonade, feeling smug and comfortable. Sometimes, when it was especially hot, we swam in the lake, and the water was so cold that we could only stay in for a few minutes at a time.

The harvest that first summer was a good one. Most aren't. Usually it rains at the wrong time, just before the harvest; then all the cherries swell and split, and the yellow jackets come out and swarm over the rotting fruit. Or it doesn't rain enough and the cherries never get full and sweet. Our first harvest, though, was perfect. I got good help, and since four acres is small for an orchard around here, it was all picked quickly while the price was high.

We made money that first season, and Clara canned many, many quarts of cherries and cherry jam. "In February we'll open one of these jars," she said, "and turn some chilly, gray morning into summer." Most of her jars, though, she wrapped in crumpled newspaper. Then she put them in boxes and sent them to New York and Texas. By the end of summer, when most of the neighbors were boarding up their windows and getting ready to leave for their winter homes, the kids still hadn't visited. "They're busy, Sam," she said to me while she put boxes on the counter at the post office, quarts of Montana summer about to be sent thousands of miles. "They'll make it out next year."

They came out sooner though, that very winter, the second winter. They came for Clara's funeral, when the road was icy, the edges of the lake frozen, and the cherry trees bowed with snow. I don't remember their visit well. I was in a bad way, spending most of my time at the kitchen table. When the kids left, I hardly noticed except that the house was colder. I often forgot to go outside for wood, and the fire died out sometimes.

One cold morning I woke in the dark and felt how alone I was; gone was the warm and familiar sound of Clara breathing next to me. I got out of bed and went to my table and sat down. Shivering there, I watched the stars fade, while out on the lake, dawn came up over Wildhorse Island. It looked out of place, like a ragged tooth. Clara and I had planned many times to make the six-mile trip to the island, but we never went. It was always something we thought the kids would like. Lots of local legends about the place: abandoned mines and homesteads, ghosts haunting certain coves, and the horses. The island had once been the home of a great herd of them. We were going to explore -- rent a boat, take a picnic lunch, look for the horses -- and then go back again with the kids, but we never did. Things got in the way. Small things, like the weather and the wind that seemed to stir the lake into a rough sea each time we got ready to go -- and the large thing, the cancer that first put Clara in bed, and then killed her.

I nearly sold the place after that and moved back to Iowa, but the friends Clara had cultivated in the summer came and visited. "Just checking up on you," Joe Sandish would say as he stomped the snow off his boots and let himself in. He'd always throw an armload of wood into the stove and exclaim, "It's a cold one today, sure enough," and we'd play cards for a spell and I would be glad for his company, for his friendship.

Another orchard owner, my age to the year, and a man whose eyes sparkled when he laughed, Joe helped me through that winter. And there were others besides Joe. George Evers, Patrick Duffy, Sheila Maloney -- they all came and visited with me, and even before spring I had stopped thinking about moving out. "This is my home now," I thought then. I still do.

Clara has been gone for more than fifteen years now. Since then I've seen a lot of harvests, good and bad. This season is at its peak now, and it's one of the rare, good ones. I will make money this year. The cherries are full, bright and sweet. The trees are at the best they've been since Clara and I came here. "Careful planning and work always pay off," she used to say. The pruning I've done, the work I've seen to, combined with this good weather -- yes, I'm glad I stayed. Clara would still be young enough to enjoy it if she were alive to see how the orchard looks today. The only trouble is my help this year, though I didn't have much choice. With all the orchards doing well, with so much fruit to pick, I was lucky to get the help I did.

They drove off the main road, down to my place, one week ago. I had a sign up, "Pickers Needed." I told them I paid top wage and that all the ladders were good ones: no broken rungs or wobbly legs. I showed them were they should park and where they could set up their tent.

The girl ruined the first bucket of cherries she picked, pulling the fruit from the stems, opening a hole to let the rot in. I said, "That's all right, I'll use those for jam." And his first bucket was nearly as bad, because he left the twin leaves on each stem, making more work than it was worth to go back and pick them all off. So I said, "Look you two, come here," and I asked them if they had ever picked fruit before, and of course, they hadn't. I should have told them then to beat it, that a peak year is not the time to learn about fruit picking, but I didn't. I let them stay, partly because I wasn't sure that I could find other help, and partly because I've become an old fool living alone out here.

Each year the help is new; the same people never come back. Fruit pickers are like that, I've learned. Migrants, mostly poor, mostly young, they aren't looking for a home. I've always worked along with them, and I've learned a lot over the years. Most seasons, though, it has taken two days to pick what good fruit there's been, so before I've had time to get to know any of my help, they've been paid and are gone, moving on to harvests in Washington and Oregon.

But this year is different. The three of us, Leslie, Ralph -- those are their names -- and I, have been working together all week and we talk. Ralph, the son of an Army officer, lived in many places growing up. He's told me stories about packing and moving and how, finally, his mother had enough and went off without explanation, leaving Ralph with his father. "I had to call him 'sir.' But it was a good childhood. I was never bored." Ralph is twenty-one, a year older than Leslie, whom he loves. And Leslie, she loves Ralph. New, fresh, neither of them really knows yet what to do -- they're still shy with each other, unsure. But when I happen to see them talking, when they don't think I'm listening, I know ... I'm not so old that I can't remember what love sounds like, and I'm glad that I didn't send them away just because they didn't know about fruit.

The first night they were here I went up to check on them before going to sleep. I wanted to make sure their camp fire was under control. They had pitched their tent in the old access road between the orchard and the south woods. Their fire was still burning -- a small, safe fire -- and I smelled its rich, piney smoke as I came up on them. When I got close, I stopped. They hadn't heard me. They were talking quietly and didn't need me there. Something, though, kept me from turning and walking away. I listened for maybe a minute. What they were talking about was simple and dear: preserving fruit. Leslie was telling Ralph how it was done, and he was listening. They were sitting together close to the fire, with their backs toward me. Ralph was holding her, his chin resting on her head, and I could tell they were both staring into the embers, letting the dying firelight touch them. I heard Leslie say, "We'll have to make preserves form some of these. We might get sick of cherries now, but this winter we'll be glad for them." Ralph answered her, "You can teach me." She turned her face up to his and they kissed and I went back to the house.

On my way I remembered how Clara taught me to preserve fruit when we lived in Iowa. It had seemed such an easy skill. Fruit, sugar, pectin. Now though, the cherries and jam I preserve each summer rarely have the flavor that Clara's did. It's only those rare batches I send away.

Leslie told me how they met. Only one month ago, in Missoula, she was awakened by a strange sound. She looked out her bedroom window and in the backyard, half hidden under a hedge, was Ralph, wrapped in a green sleeping bag, a pack next to his head, snoring loudly. "He was obviously a bum," she told me, as she reached clumsily for cherries with one hand, clutching the ladder with the other. So she called the police. "It was a stupid thing to do," she said, smiling and climbing down the ladder to empty her bucket, "but I didn't have the nerve to talk to him myself." She saw from her window how politely her backyard bum apologized to the policeman who woke him up, saying that he didn't mean any harm, was just passing through and had been tired. The she listened to the policeman telling Ralph how sorry he was to have to ask him to leave, but since someone had complained he had no choice. "Well, I figured if this guy could make a cop feel guilty, then he couldn't be a bad person, and besides, I felt rotten." So, as the police car slunk down the alley and as Ralph was just swinging his pack on, Leslie called out to him and took her turn at apologizing. They talked for a while. He was on his way to Seattle to look for work. He had a friend there. Then she invited him inside for breakfast, and that's as much as she told me.

Later, though, Ralph mentioned that coming up to Flathead Lake for the cherry season had been his idea. He had convinced Leslie to quit her job. "She deserves better," he said to me, "than to work for next to nothing, inside all day with an idiot for a boss."

I laughed then and said to Ralph, "At least here she's not working inside," and he laughed too. They've become good workers, actually. They pick fruit slowly because they're new at it. Not like the workers who've been traveling the harvest line since the time they were born. Leslie and Ralph pick slowly because they are still in awe of the fruit, concerned with each cherry. And, of course, they're slow because they often stop to look at each other, to laugh, and to take swimming breaks in the lake, rinsing the sweat and the dust away.

At the end of their second day here Ralph knocked on my door and asked if I had tools and lumber. He wanted to build a frame to hold the large cherry boxes off the ground, so the fruit wouldn't have so far to fall. That way fewer cherries would get bruised. A good idea. He had it built before dark, and I realized then that the boy was no bum. And yesterday he sketched a plan to bring lake water up to the orchard, drawing the details of a small windmill, telling me that I could build it cheaply with mostly salvaged parts. As I listened to him, I remembered how he had watched the sailboats on the lake and asked if they were out often. And I thought he was only thinking of sailing.

But Joe dropped by this evening and noticed how much of my crop still needs to be picked. "Sam, you should hire more workers. The price is going to start dropping soon." Joe's orchard is large; I pass it each day as I drive the boxes of cherries to the shipping and canning center just up the shore a few miles. Joe's orchard is almost picked clean. He has twenty pickers who nearly run up and down the ladders.

I listened to his advice, agreed, but knew that I didn't want to hire more help, even if I could find it. And Joe, friend that he is, seemed to read my thoughts, because he said, "Maybe there's no need to rush. Maybe the price will stay high this year." We stopped talking about the crop then and both of us looked out across the lake. We were standing on the dock and the sun had just gone down behind the mountains. The water was black and smooth. Nighthawks swooped close to us, catching the few mosquitoes that come out at sunset. Joe waved his arm, pointing to Wildhorse Island. "You know, all my years here, I've never taken the time to get over there," he began. "They say there are only three horses left. They say they're all mares. Sam, you and me should take a boat over someday soon."

Once on the phone, Clara and I tried to tell the kids about the island. When we told John about the horses, he said, "I saw horses in Iowa." When we told Sue about the ruins, she said, "There are enough abandoned buildings in New York. I don't need to see more." So tonight I answered Joe, "Yes, we should get over to the Island." And then I described the windmill I am going to build -- and he understood that I wasn't changing the subject -- and I talked about my children, how proud of them I have felt, and how disappointed too. In the dark this evening, talking long after the island and even the lake had disappeared, Joe said, "Some places, maybe, are for looking back and remembering; some places aren't for children." And I agreed and remembered the winter when Clara died; how the children had come and gone. I spent long hours then staring out the window, across the lake and, when night came, I stared at my own reflection in the window, as if at a stranger, a dim, flat image of a person I though I knew. I felt that I had lost everything, my wife, my children, the familiar places I had known for years, and that what I had instead was a hermitage in old age, a strange place where I was alone. That winter I was bitter, putting blame on anything I could. My sorrow was the sudden disease that killed Clara, the doctors who were unable to stop it, the wintertime with its long nights, my children who seemed unwilling to love me. But tonight, in this cool darkness after a hot day, sitting here instead of sleeping, I can look at a reflection in the same window, and this time it is of a person I know.

It's my help this year. They hardly know what they're doing, they're almost reckless. I listen to what they tell me and most of it is about what's to come. Even if only a few of their dreams turn out, they'll still be doing fine. They have plans with each other: plans for long hikes and for good jobs and land and children. The same breathless sort of plans that Clara and I shared -- not fruit picking, but looking forward. The same way Sue, with her husband, and John, with his wife, started. And tonight I remember how busy it is planning, how wonderful too. Tonight I forgive my helpers this year who are picking a cherry crop slowly, and I forgive my children who almost never visit. There will be time. Other crops, more visits.

Joe and I are going to the island. It's our plan. I want to find a bluff on it where I can stand and look back. I want to see how this place looks from a distance, from across the water. I want to imagine that Clara might be seeing me in the same way, looking at all I've done, seeing that I still have plans.

#

And to my readers who want more: the best way to encourage the publication of my next book is for my current book to receive more reviews. If you have read Paper Targets please consider leaving a review of it on Amazon. - Thank you!!!

- Success - a short story

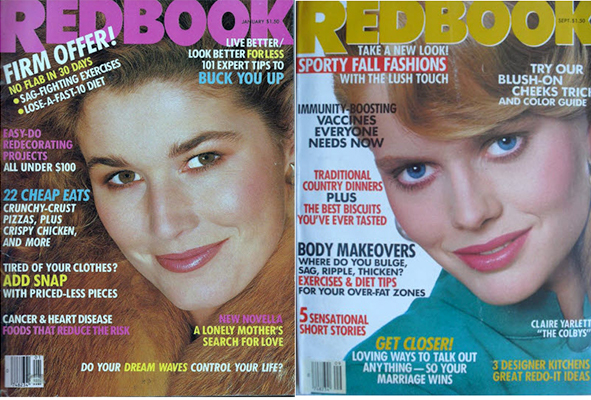

- Letter To My Daughter - a love story in Redbook (A bit about how it was published here)

- Wildhorse Island - another Redbook story

- Paper Targets, the popular novel inspired by true events.

- Boston Girl - a short story set in Missoula.

- Lies - an Enzi story

- Christmas, Seventeen - an Enzi story

- Back story of Paper Targets

- FreeMail - some of what happened

- PVO - remembering a friend

- Dyslexia, the advantage

- Leaving Home - a rememberance

- R/V Wecoma, On the route to becoming a shellback

- Contact and follow:

- Instagram @SteveSaroff

- Facebook steve.saroff

- LinkedIn SteveSaroff

- Threads: @stevesaroff

- GoodReads: Steve S. Saroff

Return to Top of Page

(c) 2023 Steve S. Saroff & Saroff Corporation www.saroff.com

Author. Start-up consultant. Adviser to artists, writers, and a few good actors.